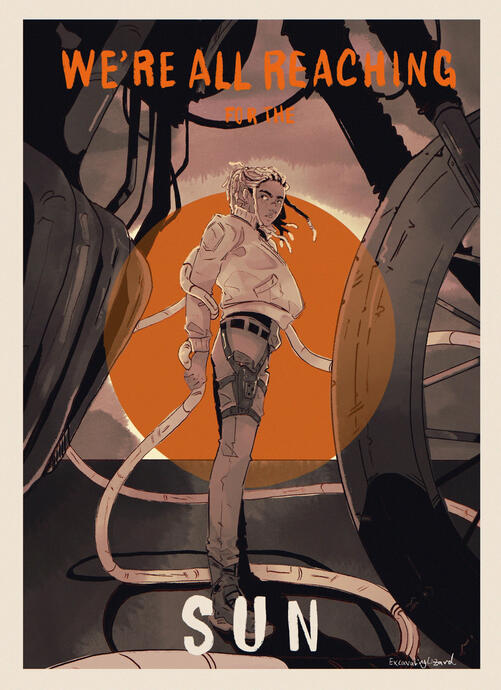

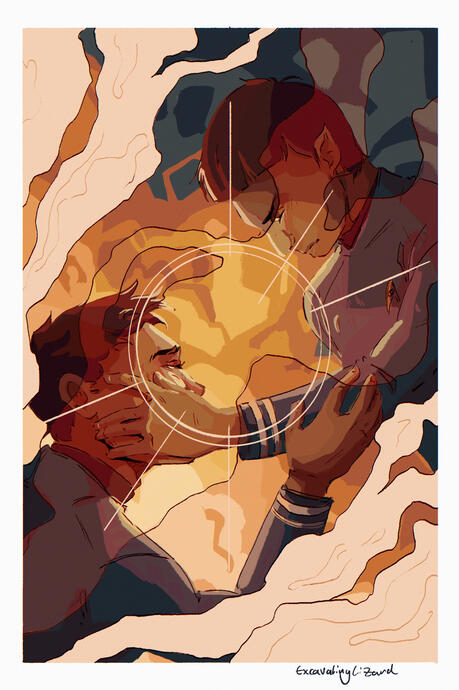

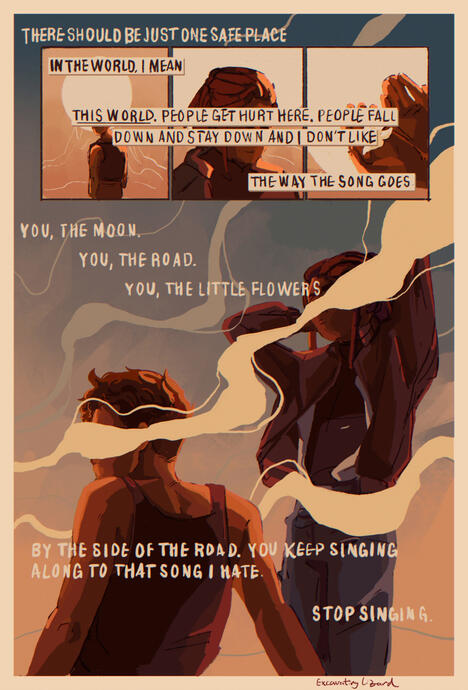

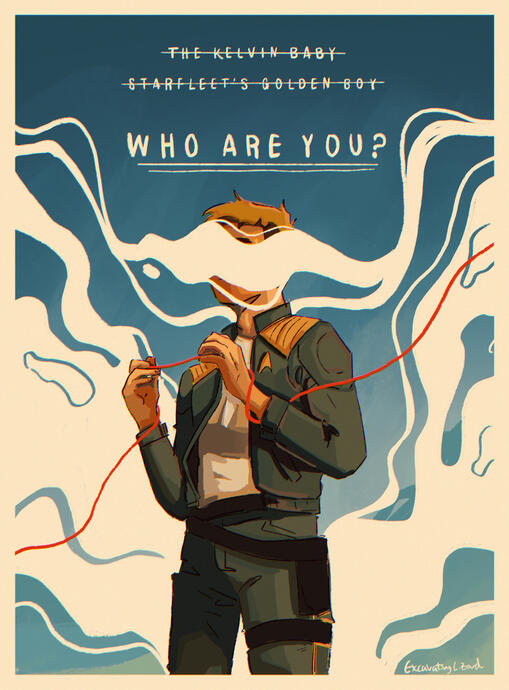

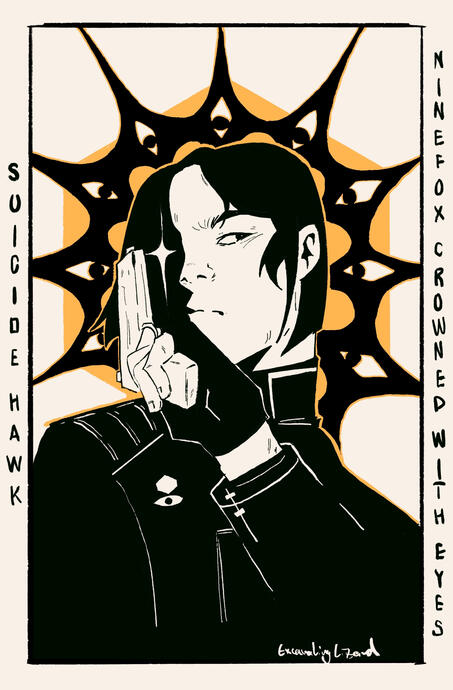

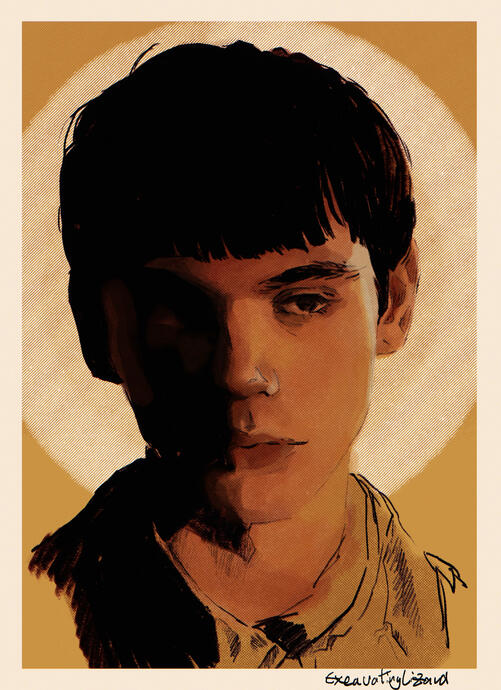

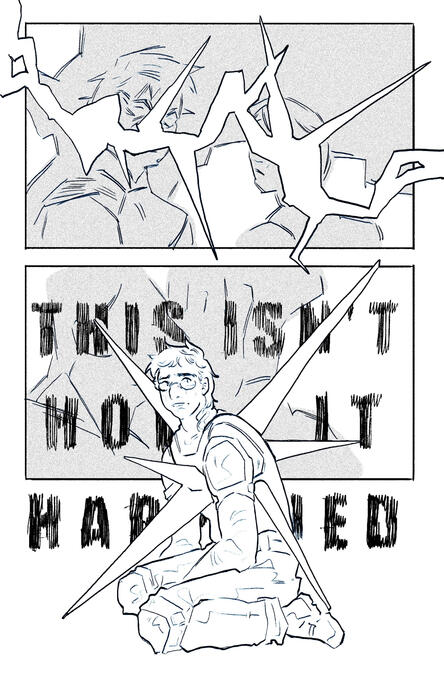

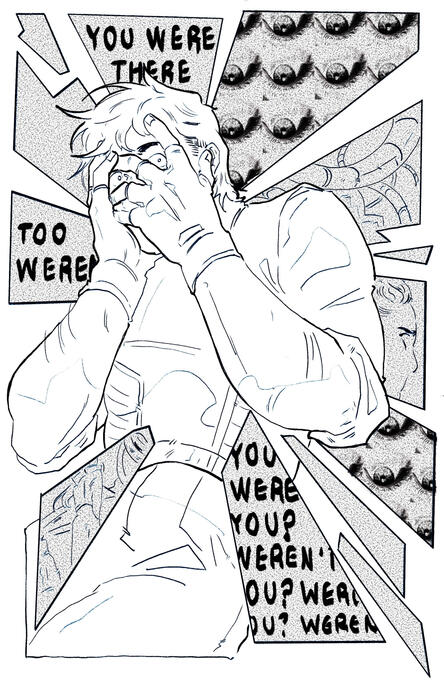

ExcavatingLizard - Portfolio

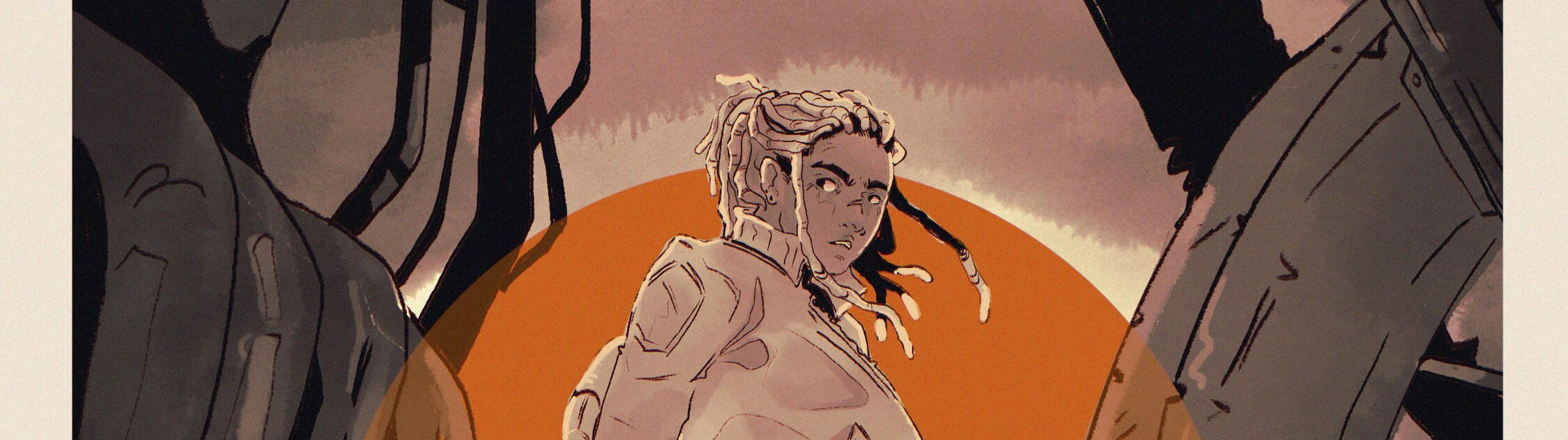

Hi, I'm Lizard. My work is mostly composed of digital illustrations and fanart, but this portfolio will also include traditional studies and paintings.

My work includes: comics, illustrations, visual novel games, and animations

Commision Status: CLOSED

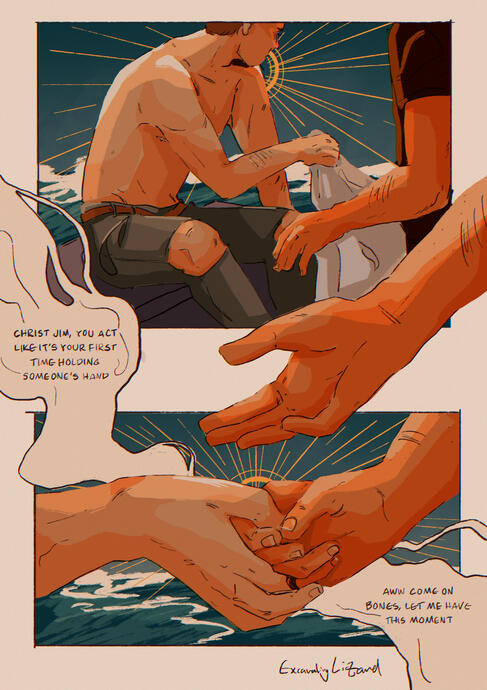

ILLUSTRATIONS

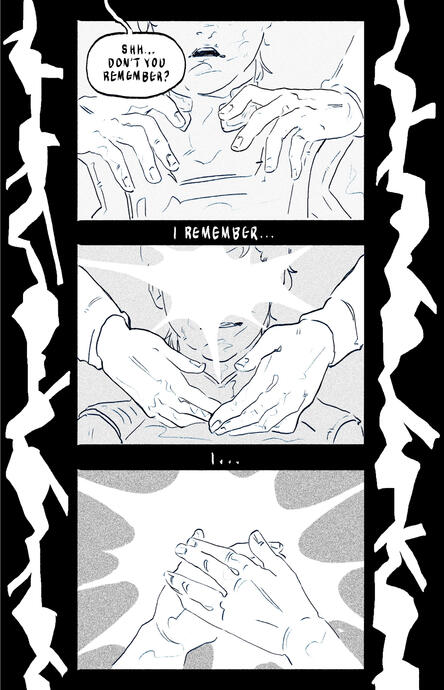

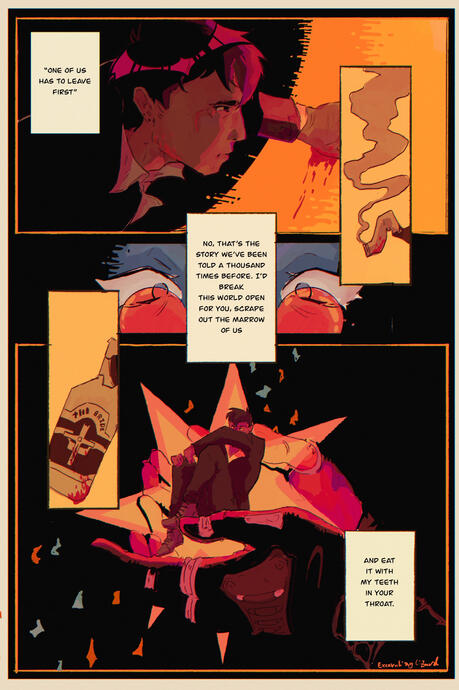

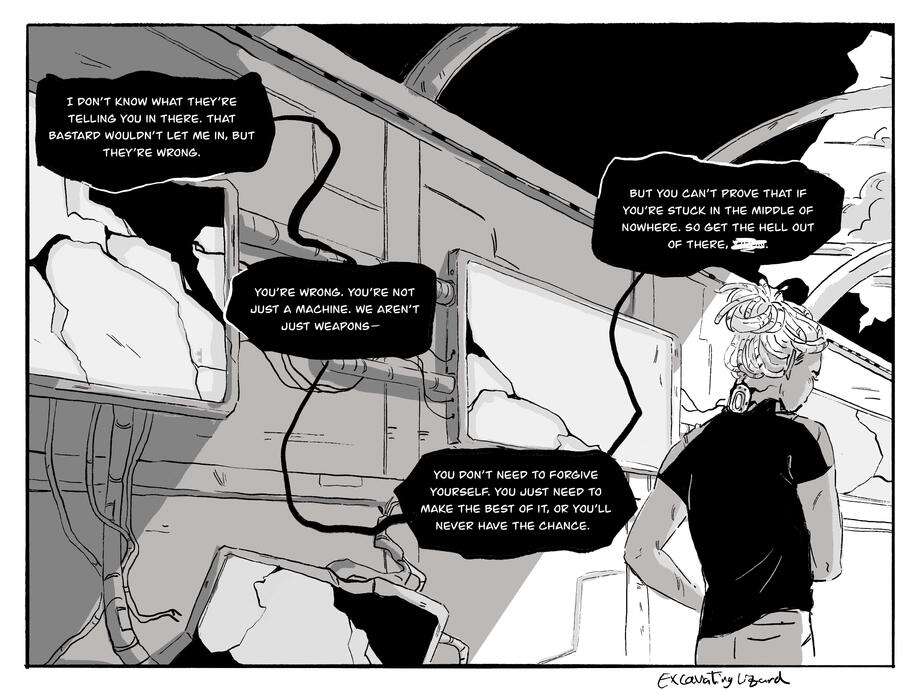

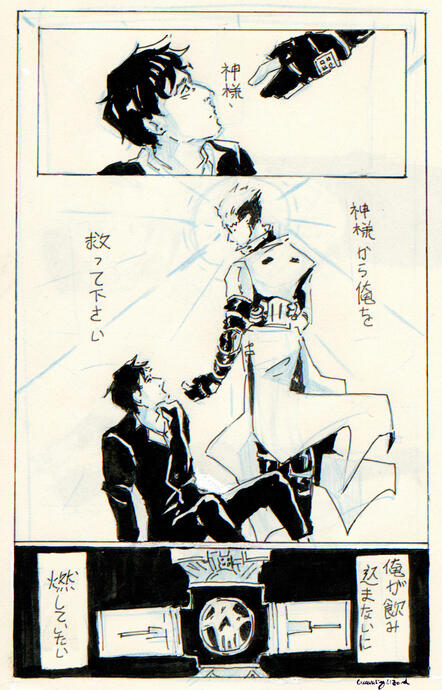

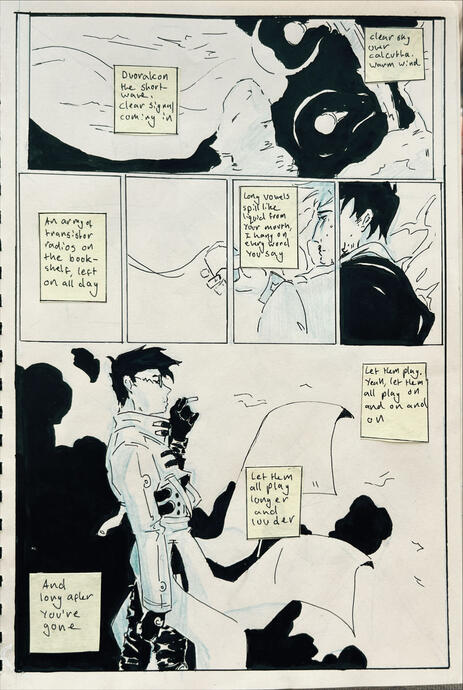

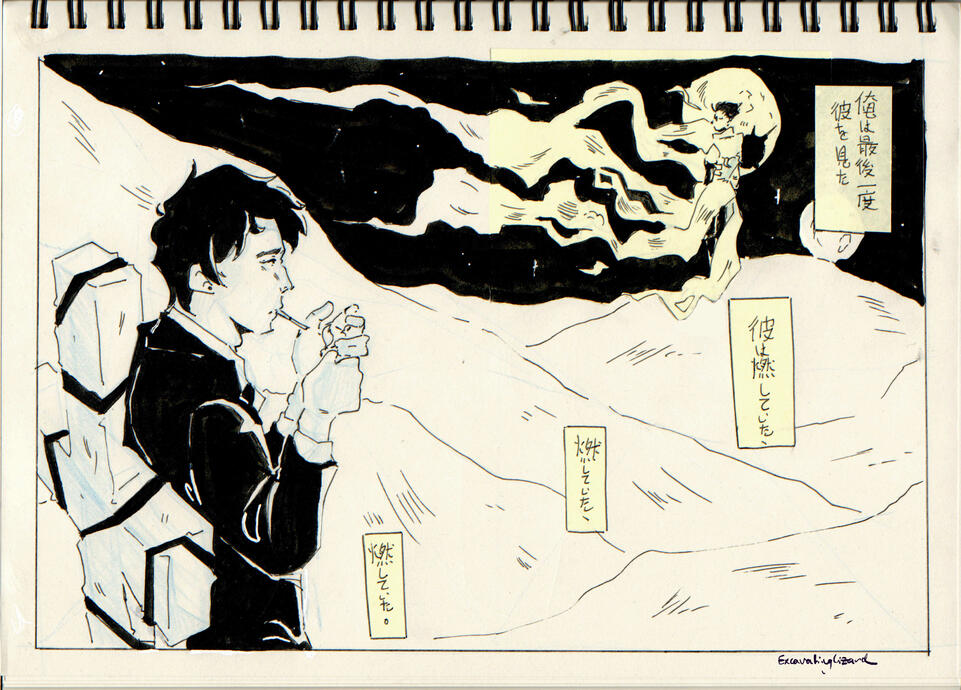

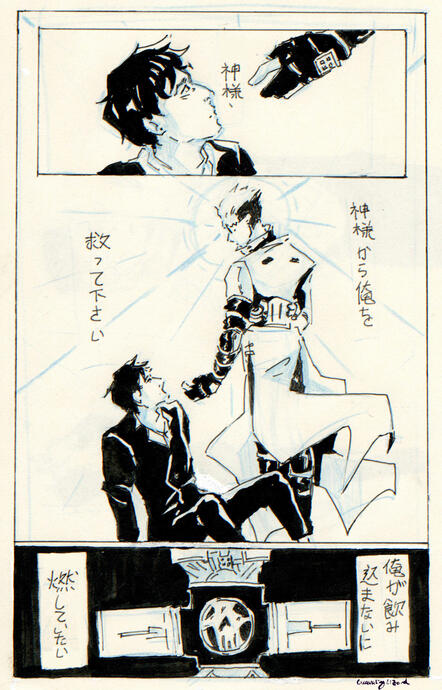

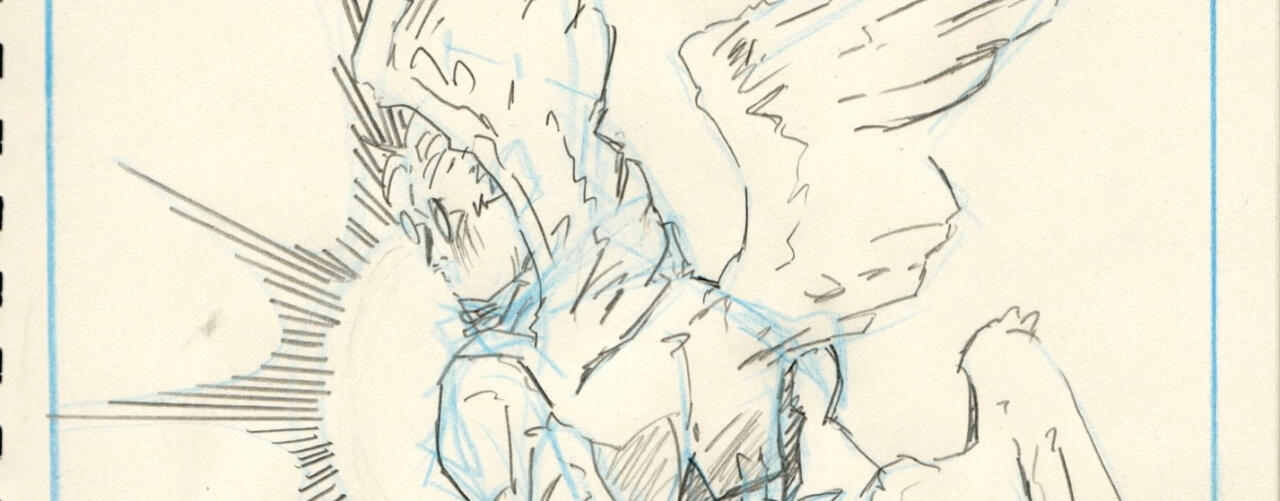

COMICS

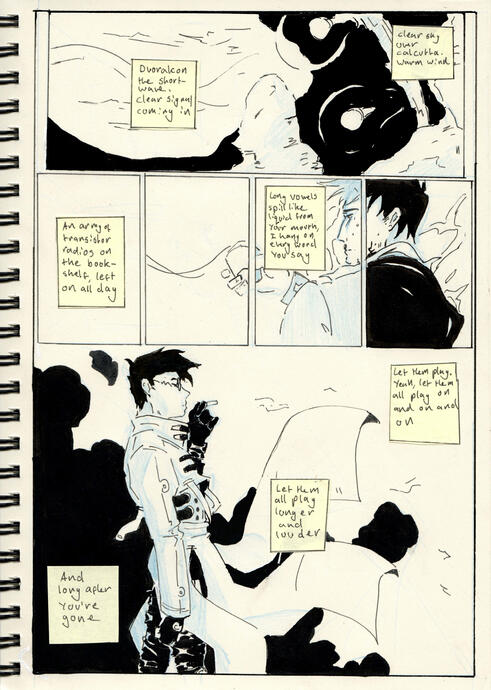

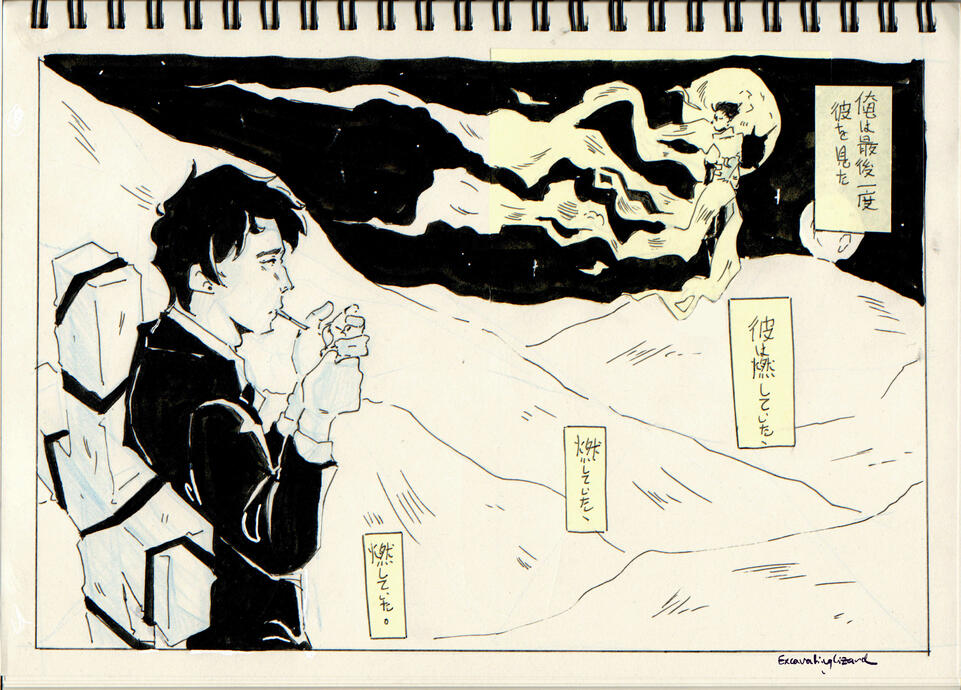

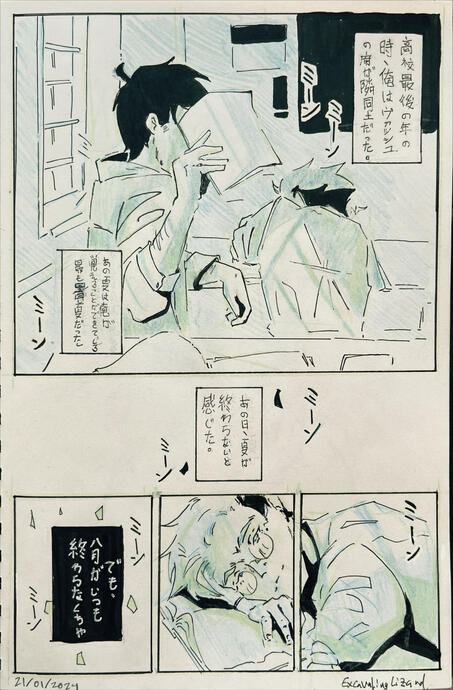

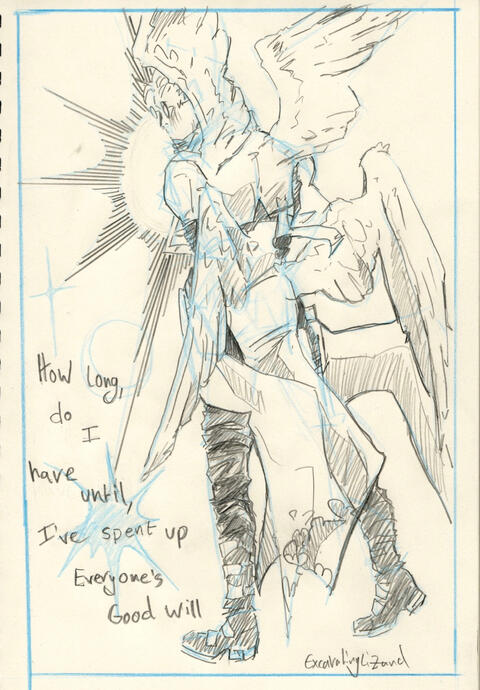

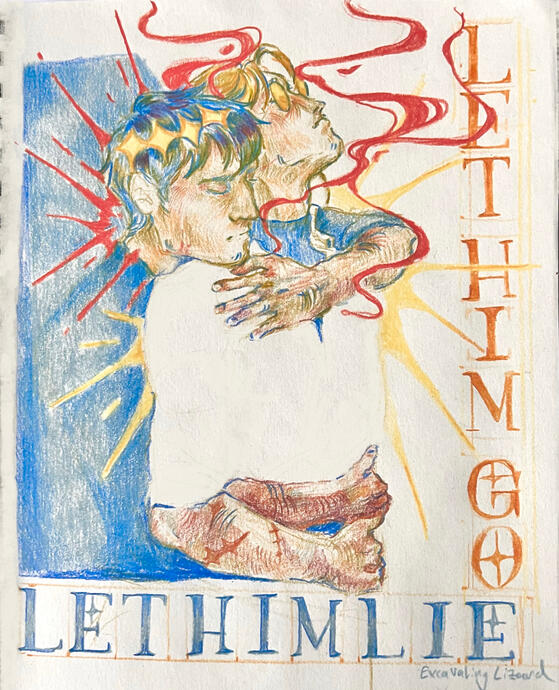

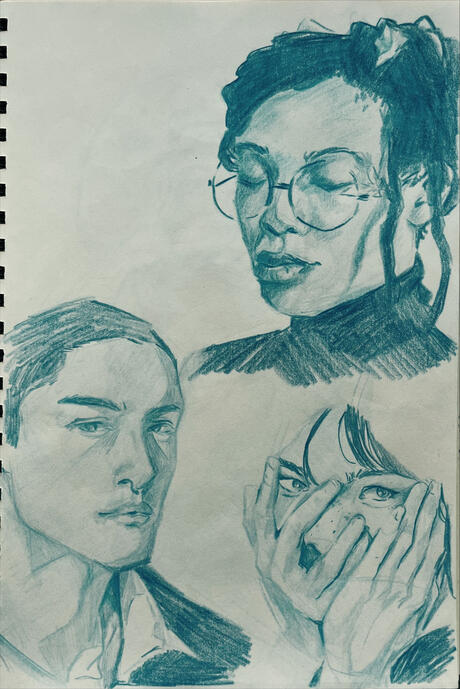

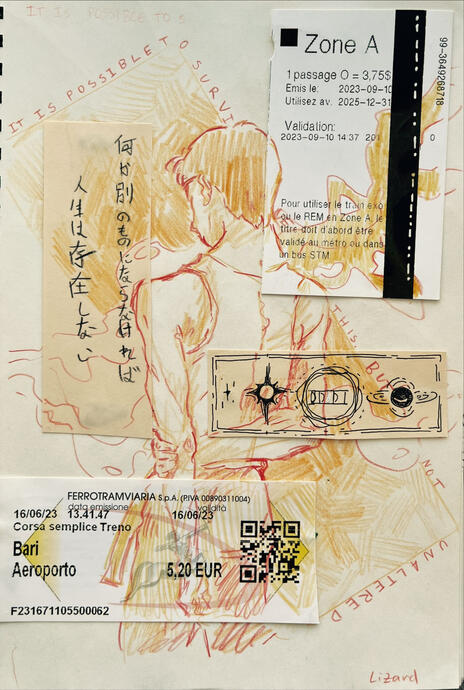

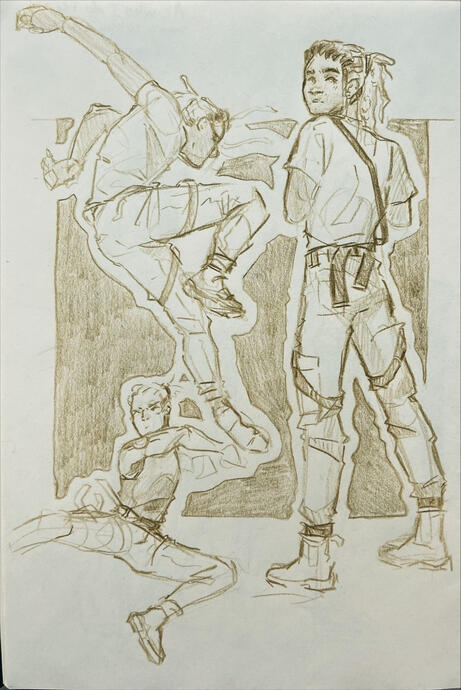

SKETCHBOOK

YOU CAN GET THE REST OF THIS SKETCHBOOK ON MY ITCH.IO

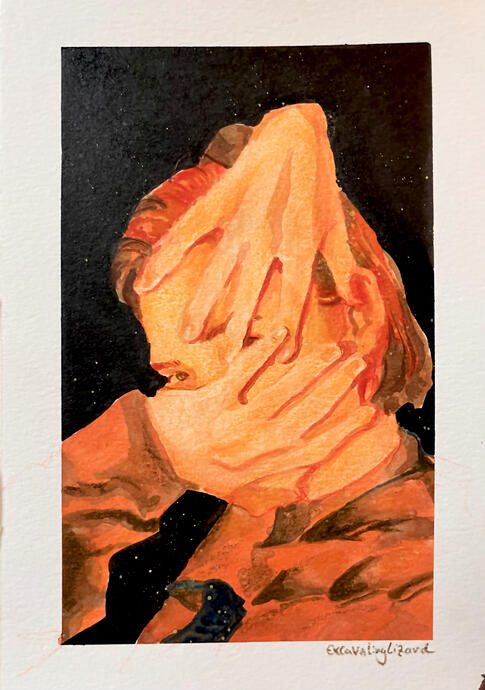

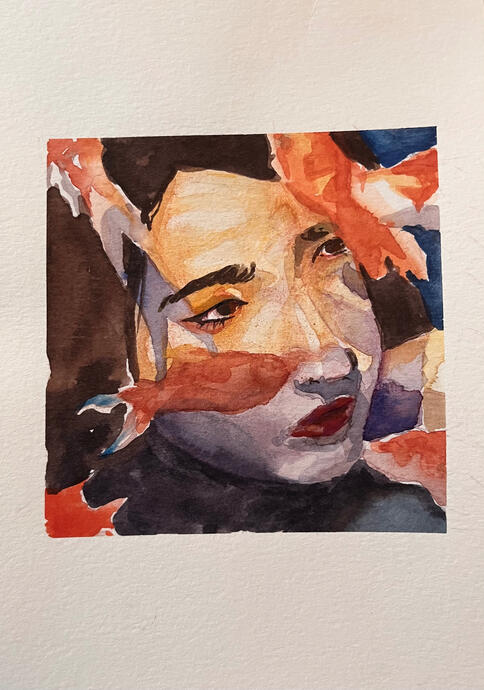

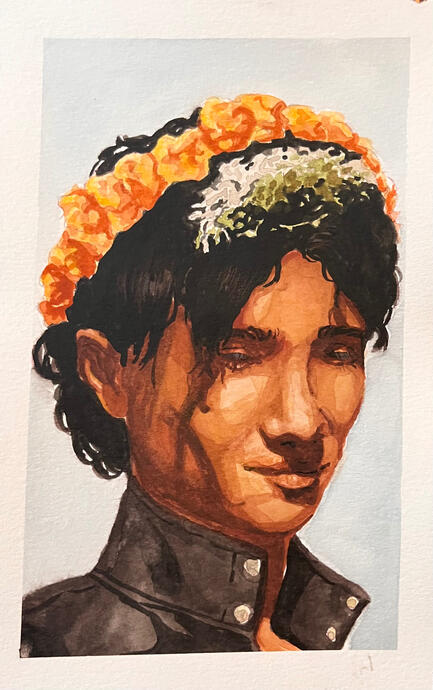

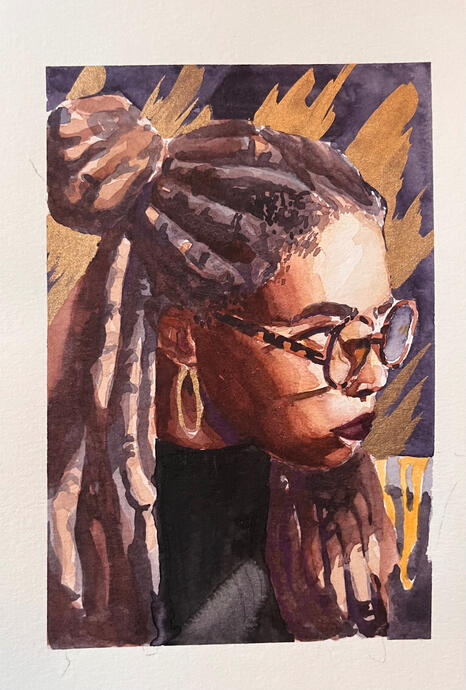

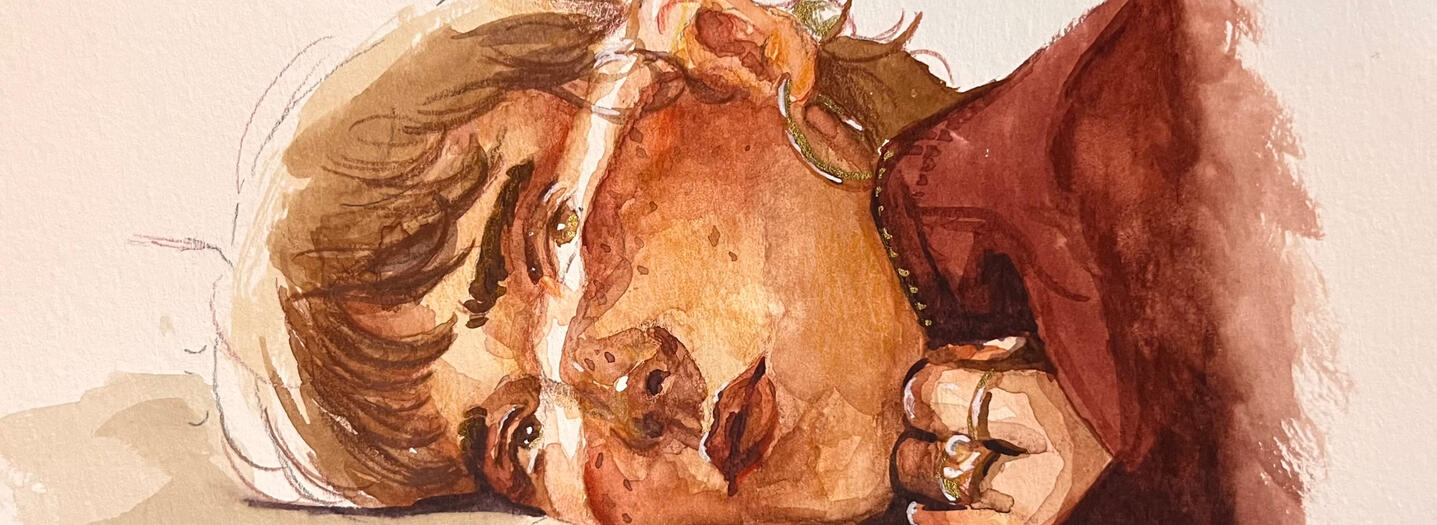

Watercolours

What is the point?

(or, a needlessly thorough complaint about The Martian)

Andy Weir's 2011 book The Martian was a smash hit--it's not often you see a book with a 4.42 Goodreads rating from well over a million reviews. Initially self-published, Weir's debut novel soon got picked up by a traditional publisher and promptly sold over five million copies. Besides being a hit success, one of the things that The Martian was most lauded for was its emphasis on realistic science. With a book as popular as The Martian, it's no surprise that Weir has become many people's first introduction to science fiction.Science fiction has, in some form, been around for thousands of years (I'd recommend taking a look at a summary of A True Story), but it was really around the early to mid 20th century that the genre reached a form that we would recognize today. The meteoric rise of science fiction through the 20th century was driven by rapid technological advancement and defined by the fractured political climate of the cold war and civil rights movements.All the same, despite its vast presence in the literary canon, the merit of science fiction has often fallen under speculation. Many authors whose work could be recognized as science fiction--or at least following tropes common in the genre--have refused the classification. Authors like Margaret Atwood and Stanisław Lem have gone so far as to actively spurn the label of science fiction, with Atwood criticising the genre as 'talking squids in outer space' (Langford, 2003). Science fiction never quite made it into the mainstream literary world, and with the death of many of the magazines that had defined the landscape of the 60s and 70s, the genre fell into an equilibrium: not quite 'real literature', but not quite easy reading, plagued by overzealous fans and gatekeeping.When a book gets as suddenly popular as The Martian, it attracts readers outside of the genre. Maybe they've picked up a couple paperbacks, maybe they've read Asimov or tried their hand at Dune, or maybe The Martian is the first science fiction they've ever read. How many people have come to me and, on learning of my love of the genre, told me that they don't really read sci-fi, but read The Martian a couple years and loved it? How many have announced that they only read Weir?This is real sci-fi, I've been told, though perhaps not in those words, enough pseudoscience, this guy knows what he's talking about.The Martian can be classified as 'hard science fiction', which, in the standard definition, can be summed up as 'the math works' (Gladstone, 2016). Essentially, any science fiction story which focuses on science and technology that, if not actually present in our current time, could be explained and properly quantified by our modern understanding of science. Of course, Weir didn't invent hard science fiction. While sci-fi may have always fallen under scrutiny from the literary world, certain works have managed to slip their way into the mainstream as 'serious' literature. These works often, though not always, leaned further into what we might classify as hard science fiction, including authors such as Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, and Arthur C. Clarke, not to mention Ray Bradbury and George Orwell. It can be easy to dismiss science fiction as 'talking squids in space'--less so, perhaps, when the math works.Hard science fiction is not without its critics. Perhaps more accurately, the insistence on raising 'hard' science fiction on a pedestal above its softer counterparts can bring up questions on what we as a society assign value to. For one thing, what do we even classify as 'hard' sci-fi? What, then, is 'hard' science? Ursula K. Le Guin criticized the divisions drawn between hard and soft science fiction, explaining how so often hard science fiction writers focus only on engineering, physics, and math, with perhaps a bit of astronomy or chemistry sprinkled in for variety. "Biology, sociology, anthropology—that's not science to them, that's soft stuff," Le Guin stated in a 2013 interview, and went on to explain: "They’re not that interested in what human beings do...I draw on the social sciences a great deal." (Le Guin, 2013). Furthermore, the preoccupation with and exaltation of realistic science ties into a further point of contention in the obsession with declaring a work of science fiction as 'prophetic'. George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four is often lauded as predicting the surveillance state, the rise of extremism, and governmental control, but...Nineteen Eighty-Four wasn't a prediction. It was a commentary.Science fiction rose to popularity when it did because it provided a vehicle with which the changing landscape of the world could be explored and understood. Science fiction has always been at its strongest when it is used to explore themes of technology and humanity's place in the world, of inequality and empire, of advocacy and social identity (Kilgore, 2010). At the end of the day, Starship Troopers, the Foundation series, and Nineteen Eighty-Four have survived in the public consciousness for as long as they have because they had something to say. We can recognize stories like Nineteen Eighty-Four and Zamyatin's foundational We in our current reality, not because they predicted the future, but because they were addressing issues of the time which are still relevant today.What, then, is the point of The Martian? What great secret of the world and society is Weir laying bare?The answer is, well, nothing. The Martian is a romp across the surface of an inhospitable world, a tale of one man's ingenuity and the commitment of his teammates. It's a survival story following in the footsteps of Robinson Crusoe and the rest of the genre, and it is, frankly, a good read. Kevin Nance's review sums up The Martian as follows: "Mark's unflappability, perhaps the book's biggest asset, is also its greatest weakness. He's a wiseacre with a tendency to steer well clear of existential matters. Despair, resignation, self-doubt...are not for Mark." (Nance, 2014).Ultimately, hard science or not, The Martian is entertainment, and that's absolutely fine.Even if The Martian may not explore the depths of the human condition or the state of our society, it still has value. So much of the publishing industry is built on the kind of literature that people enjoy because they are simply a good time. There needs to be space for these books, whether it's another story about a guy eating potatoes on Mars, a thriller you pick up at the airport W.H. Smith, or the newest Romantasy sensation. Frankly, considering the treatment and constant dismissal of genre fiction, those books we brush off as mindless entertainment might have quite a bit more going on under the surface. If nothing else, The Martian brought so many new readers into an incredibly diverse genre, some of whom may never have been brave enough to dip their toes in without it.Ultimately, the issue is not with Andy Weir or Orwell, but with the people who look at these books and turn to those that may focus on the social sciences, or even those works completely divorced from our current reality, and declare them pointless. Literacy rates are declining around the world, and critical reading skills are becoming all the more rare even as their value skyrockets in our current age of misinformation. Being able to read beyond surface level interpretations and understand the themes of a work is a skill, and it’s one that we’re losing. It's easy to deride science fiction as mindless when you ignore its purpose and the methods through which it achieves that end. You do not need to see the future to open your eyes to the world around you. Maybe you just need to learn to hear what the talking squids are saying.

References

Gladstone, M. (2016, January 21). How Do You Like Your Science Fiction? Ten Authors Weigh In On ‘Hard’ vs. ‘Soft’ SF. (F. Wilde, Interviewer)

Le Guin, U. K. (2013). (Paris Review, Interviewer)

Kilgore, D. W. (2010). Difference Engine: Aliens, Robots, and Other Racial Matters in the History of Science Fiction. Science Fiction Studies, 16-22. doi:10.1525/sfs.37.1.0016

Langford, D. (2003). Bits and Pieces. SFX magazine(107).

Nance, K. (2014, February 17). Astronaut is lost in space in thrilling 'Martian'.